For adults who are attempting to cope with traumatic events from the past, healing and moving on can prove to be a daunting task. Haunted by negative memories and thoughts, individuals may become stuck in their own sense of victimization and come to view themselves as vulnerable persons who will never truly get beyond their traumas. Adaptive coping in the wake of a traumatic past can be a long, difficult, and highly challenging road. However, with professional assistance that focuses on accessing one’s resources (internal and external), coupled with a great deal of determination and perseverance, those suffering from childhood trauma can look forward with hope and optimism. The following represent some tips that may be helpful when attempting to cope with past childhood trauma.

1. Live each moment in the present, rather than the past. Become familiar with Zen meditation and mindfulness. Buddhist philosophy has much to teach about living in the present as a way to live life to its fullest.

2. Although we cannot change our past, we can actively change and “re-script” the way in which we respond to our past and the way we view ourselves today. Although you may have been victimized in the past, viewing yourself as a “victim” who is hopelessly trapped in an ongoing state of victimization is not likely to lead to a life of happiness, fulfillment, or contentment. Work on viewing yourself instead as a survivor and a thriver who actively contributes to your own present and future well being.

3. Stay away from unhealthy coping mechanisms such as drugs, alcohol, and unhealthy relationships. These will only serve to keep you stuck, increase the harm to your body and mind, and prevent growth. While they may serve to distract and offer some short-term relief, in the end they will only bring you long-term grief (short-term relief and long-term grief).

4. Be open about your past experiences and don’t be afraid to talk about them with others. Allow yourself to feel anger towards those who hurt you, but be careful not to get “stuck” in your anger. You want to be able to feel your anger, work through your anger, and then get beyond it. Falling prey to, and becoming a prisoner of, your own anger is a sure recipe to a miserable, unhappy life.

5. Counselors /therapists can be a helpful resource in offering you support as you continue on in your quest for meaning and self-actualization. Be sure to seek out counselors / therapists / healers who are capable of helping you to process, work through, and move out of and beyond your emotional distress, as well as to help you “create” meaning out of your life and life experiences.

About the Author:

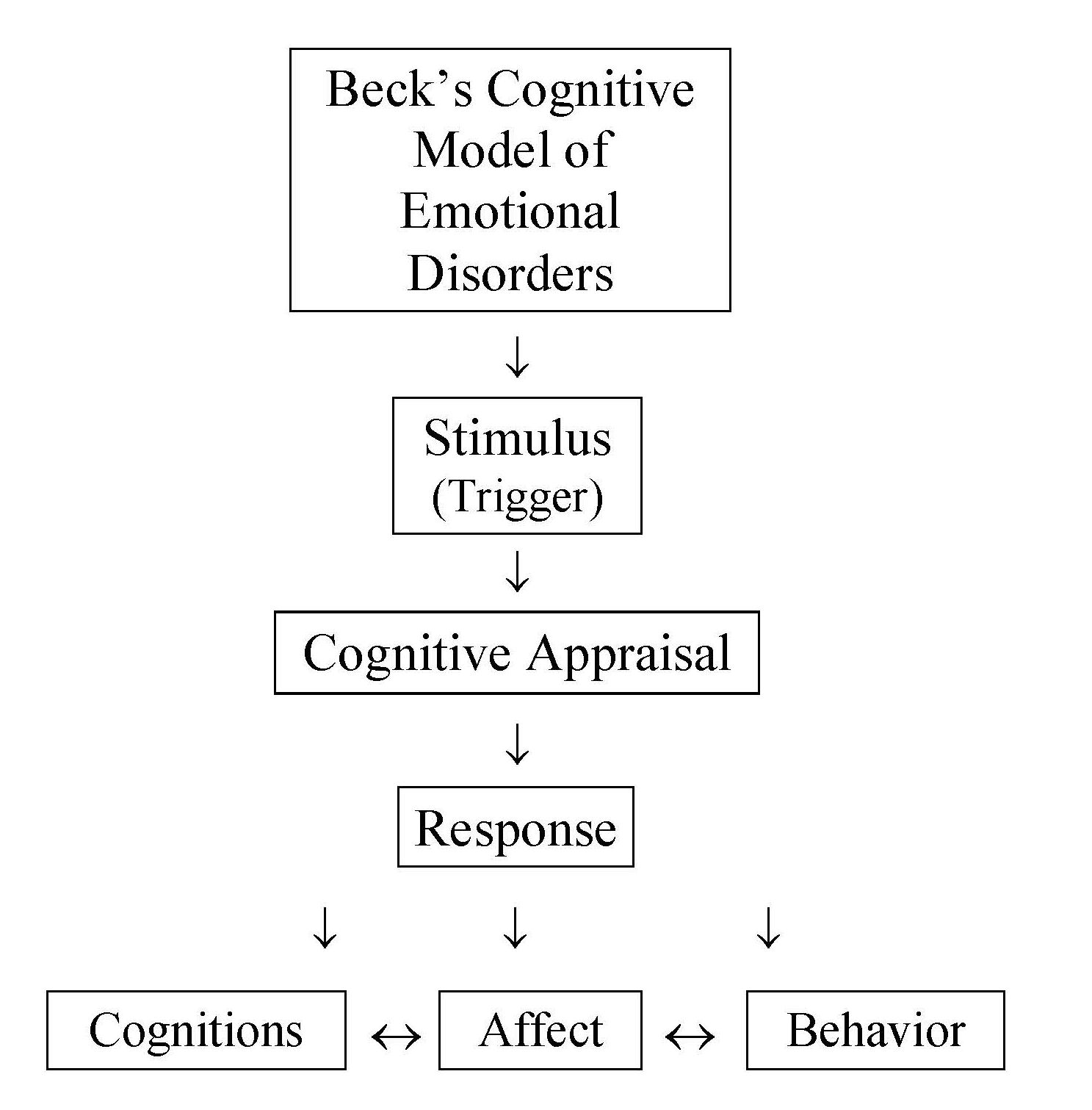

Mervin Smucker specializes in behavioral cognitive therapy as a practicing psychologist and medical professional. Well respected in his field, he continues to speak at conferences around the world and provide material for publications in a number of medical journals. Dr. Smucker has completed immense research and study in the area of child abuse and its effects on the brain. Mervin Smucker has worked to integrate imagery rescripting and reprocessing methods to help patients cope with such events.